NEWS

Telehealth: “Should I Stay or Should I Go…?”

August 17, 2022 | By Marissa Moore, CFA

Second Opinion

Up until a few years ago, the prevailing perception of telehealth was that it was some futuristic, Jetson-like nice-to-have for a limited set of use cases. Of course, this was misguided, but it really wasn’t until the Covid-19 pandemic when the illusion was finally shattered.

Now, nearly 40% of US patients see doctors virtually. Roughly 85% of physicians use telehealth, with 60% saying it enables them to provide high quality care and 44% saying it reduces the costs of care. And according to a recent analysis by Omada Health and my colleague Christina Farr, 30% of care could theoretically be virtualized under existing CPT codes.

But we’re nearly three years into this saga, and there’s still no real certainty about what support there will be for telehealth — from a federal level — when the public health emergency ends.

Why are patients, providers, and payers stuck in this never-ending limbo land? How many times can we kick the can down the road? Where’s the beef??

I spent the last month chatting with some of health tech’s most active lobbyists and government affairs folks, combing through federal lobbying reports, and tracking Congressional legislation to get a better picture of how telehealth advocacy is materializing and where reform might be headed. I also explored some of the different strategies healthcare startups can take to influence policy and the cost/benefit analysis involved.

Lobbying on the whole is generally viewed as a negative trend, associated with things like e-cigarettes, Big Pharma, and bad agriculture. But in telehealth, it’s truly a mixed bag. Experts I spoke to felt that in certain areas, more flexibility is needed to really get truly internet-based approaches to health care up and running, especially at a time when access is so limited in certain parts of the country. What’s the harm, for instance, in allowing doctors some more freedom to speak with a patient on a number of different compliant video platforms? That said, examples like Cerebral — where reporters, ex-employees, and regulators have alleged that patients were receiving controlled substances online without proper quality controls — have shown us a potentially dark side. Too much freedom can lead to patient harms.

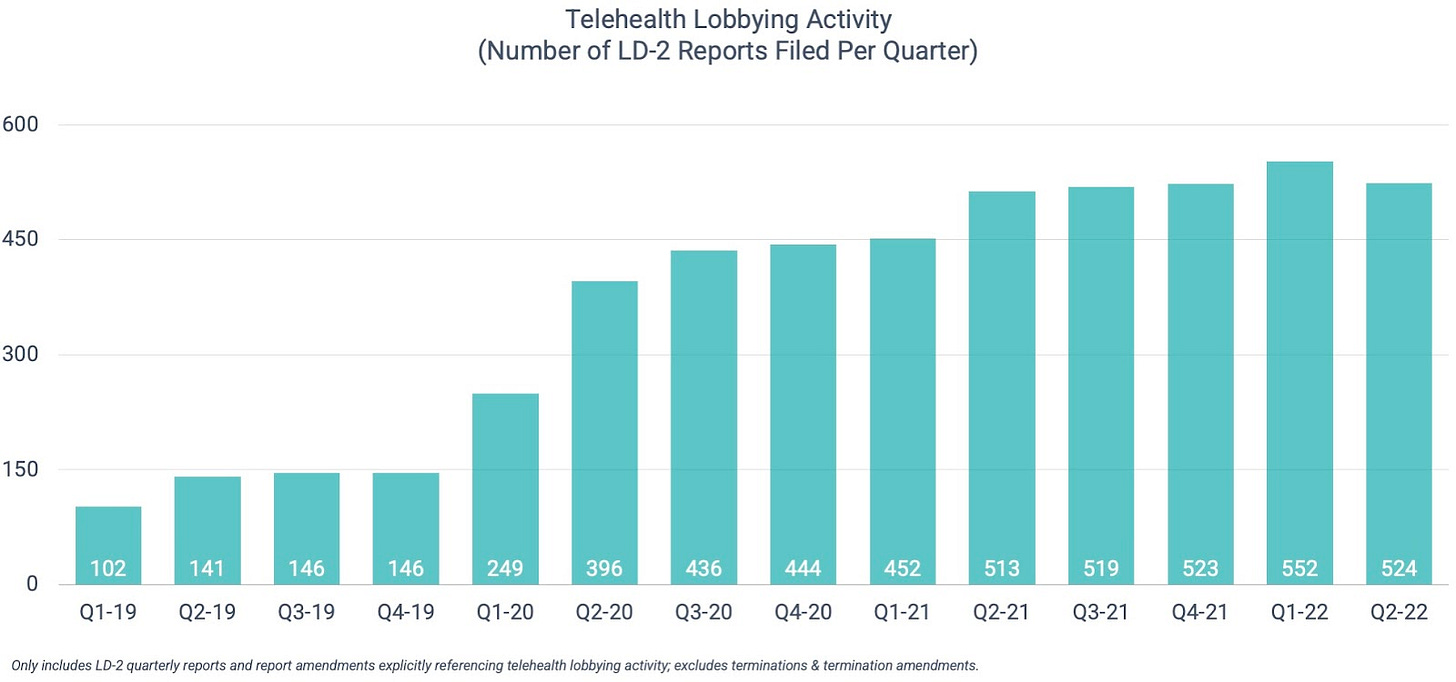

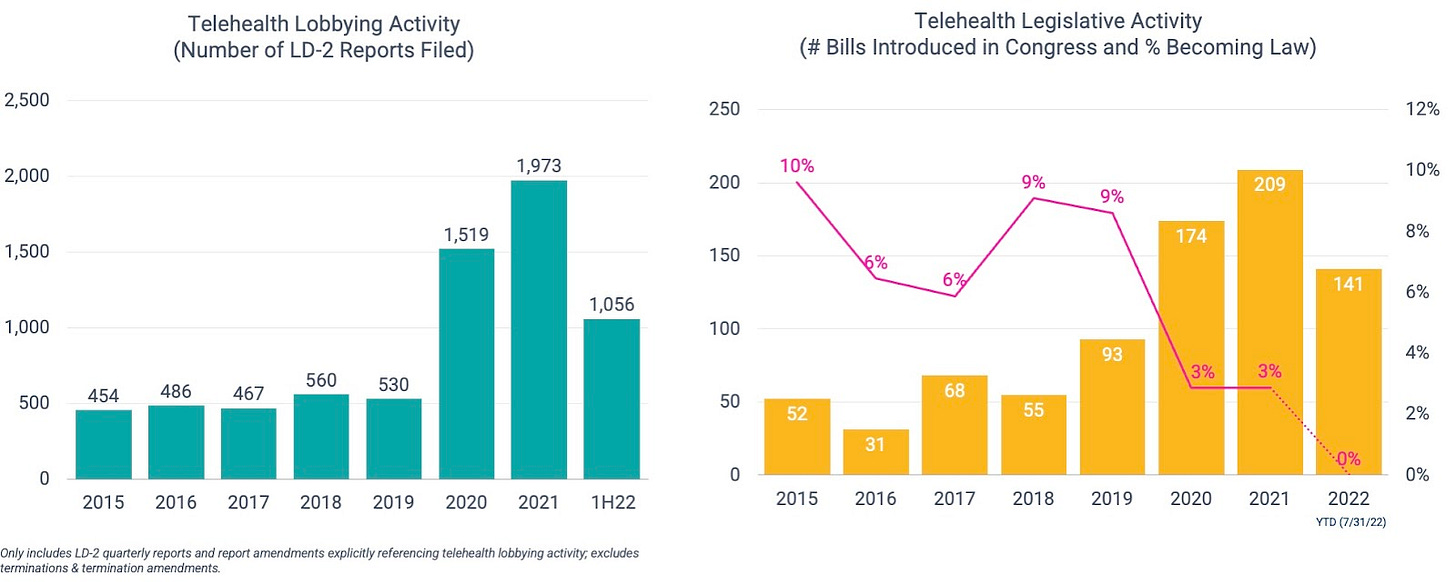

Telehealth lobbying activity

Two and a half years into the Covid-19 public health emergency, telehealth lobbyists remain busier than ever. The issue has been cited in more than 500 federal lobbying reports in each of the last five quarters (vs. Q1’19-Q4’20 average of 258). Coming in slightly behind Q1’22, Q2’22 represents the second-most active quarter on record with 524 reports filed. In aggregate, the Q2’22 reports disclosed nearly $260 million in associated spend.

I’ll dig into the specific issues in a bit, but first it’s important to understand who’s sponsoring the agendas.

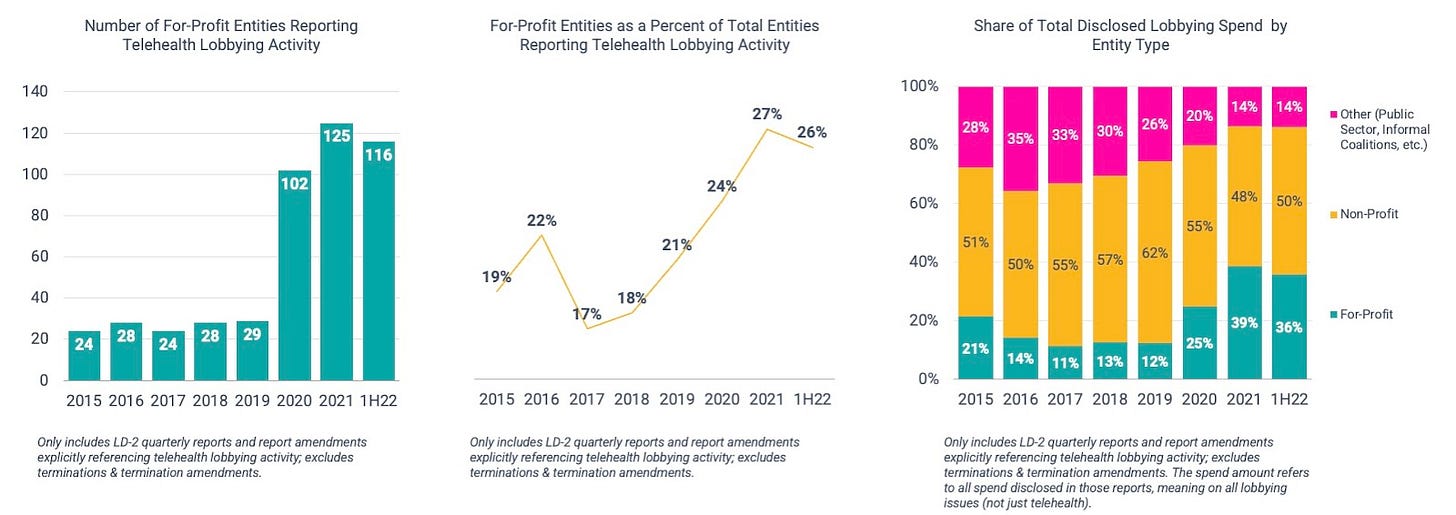

Non-profit charitable organizations and industry associations — like America’s Health Insurance Plans (AHIP) and the American Medical Association (AMA) — almost always make up the lion’s share of federal lobbying activity, and that’s certainly the case here. But for-profit involvement has ticked up noticeably since the beginning of the pandemic.

As shown below, the number of for-profit entities actively lobbying remains significantly elevated vs. the pre-pandemic period. The same can be said of their lobbying spend. For-profit organizations — which, again, only represent 26% of all LD-2 filers — account for 36% of lobbying spend (~$92 million) so far this year. That compares to a historical average of ~14% (2015 – 2019).

These for-profit advocates span everything from publicly-traded behemoths to privately-held, early-stage startups. Some have been active for years (e.g., Teladoc, Elevance (fka Anthem), Included Health, Philips), while others have only started to get involved this year (e.g., LabCorp, Merck, Oak Street Health, Hinge Health).

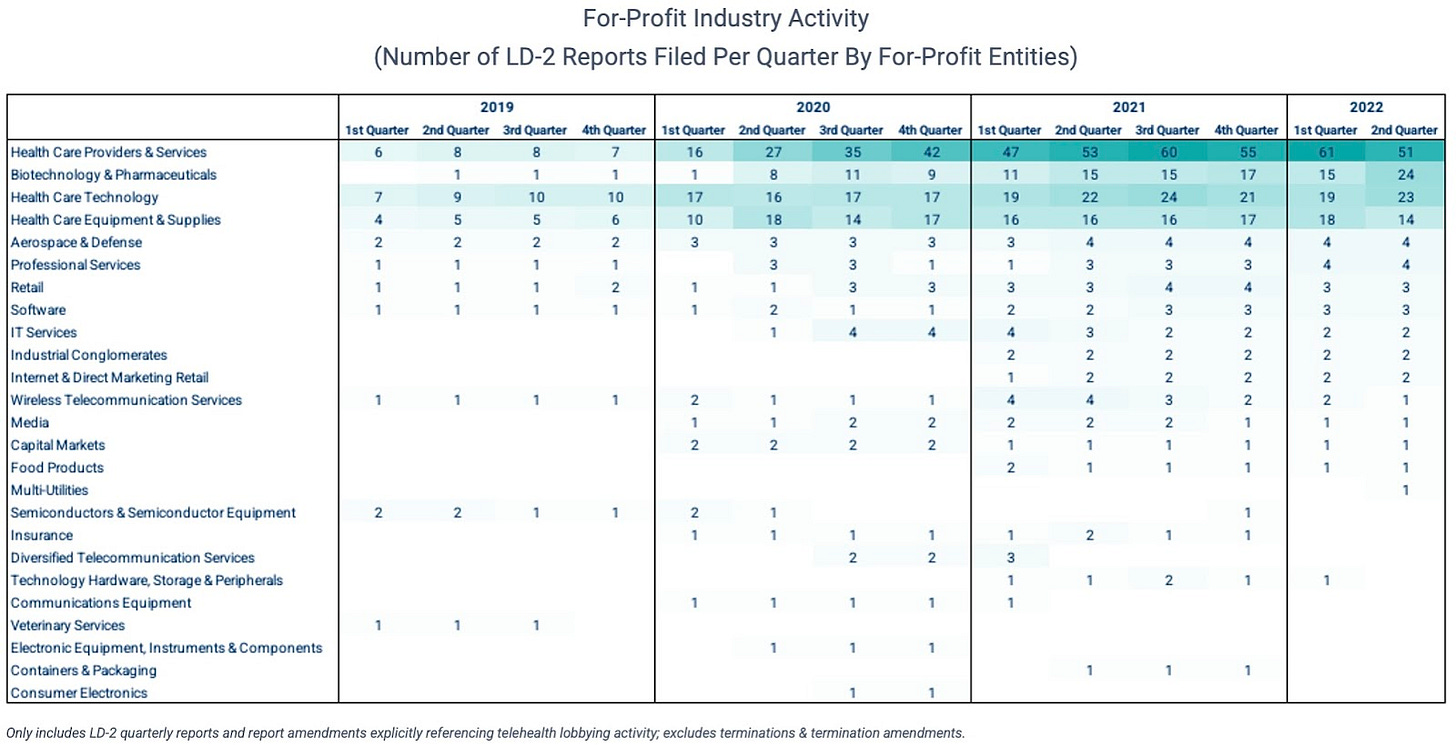

And while payers and providers certainly make up the majority of for-profit activity, other industries like biopharma are rapidly accelerating their involvement. And several other industries outside of healthcare are taking interest.

So what are they advocating for?

Well, first it’s important to note that some of the biggest issues actually predate the pandemic. These include:

- Expanding telehealth coverage under Medicare,

- Private insurance-related issues like how to pay for telehealth under high deductible health plans and health savings accounts

- Correcting for unintended consequences of the “practice of telemedicine” exceptions in the Ryan Haight Act (which in essence blocked clinicians from prescribing controlled substances online without first seeing patients in person)

These issues — with some incremental, pandemic-specific nuances — remain a large focus today. But the sheer volume and diversity of advocates is absolutely unprecedented.

“The pandemic blew it out,” said Dean Rosen of Mehlman Consulting. “You went from a handful of for-profit companies that were trying to sell Medicaid MCOs and Medicare (e.g., Amwell, Teladoc, and some behavioral health startups) to suddenly everyone caring about it.”

Why would companies not serving Medicare populations suddenly care about Medicare flexibilities?

“Because it’s a business opportunity,” said Rachel Stauffer, a Senior Director at McDermottPlus Consulting. These companies may not sell to Medicare right now, but they may want to in the future. There’s also a hope that Congressional legislation would lead to a “rising tide,” where private insurers follow Medicare’s lead.

The House’s recent passage of the Advancing Telehealth Beyond COVID–19 Act of 2021 — which would extend Medicare flexibilities through the end of 2024 (if approved by the Senate and signed into law by President Biden) — would be a big step in the right direction. But at the end of the day, it’d still be another “kick the can down the road” exercise, and telehealth advocates want to see more permanent reform put in place.

And then, of course, new interests have emerged in response to the pandemic. For example, there’s growing interest in using telehealth to expand access within very specific verticals.

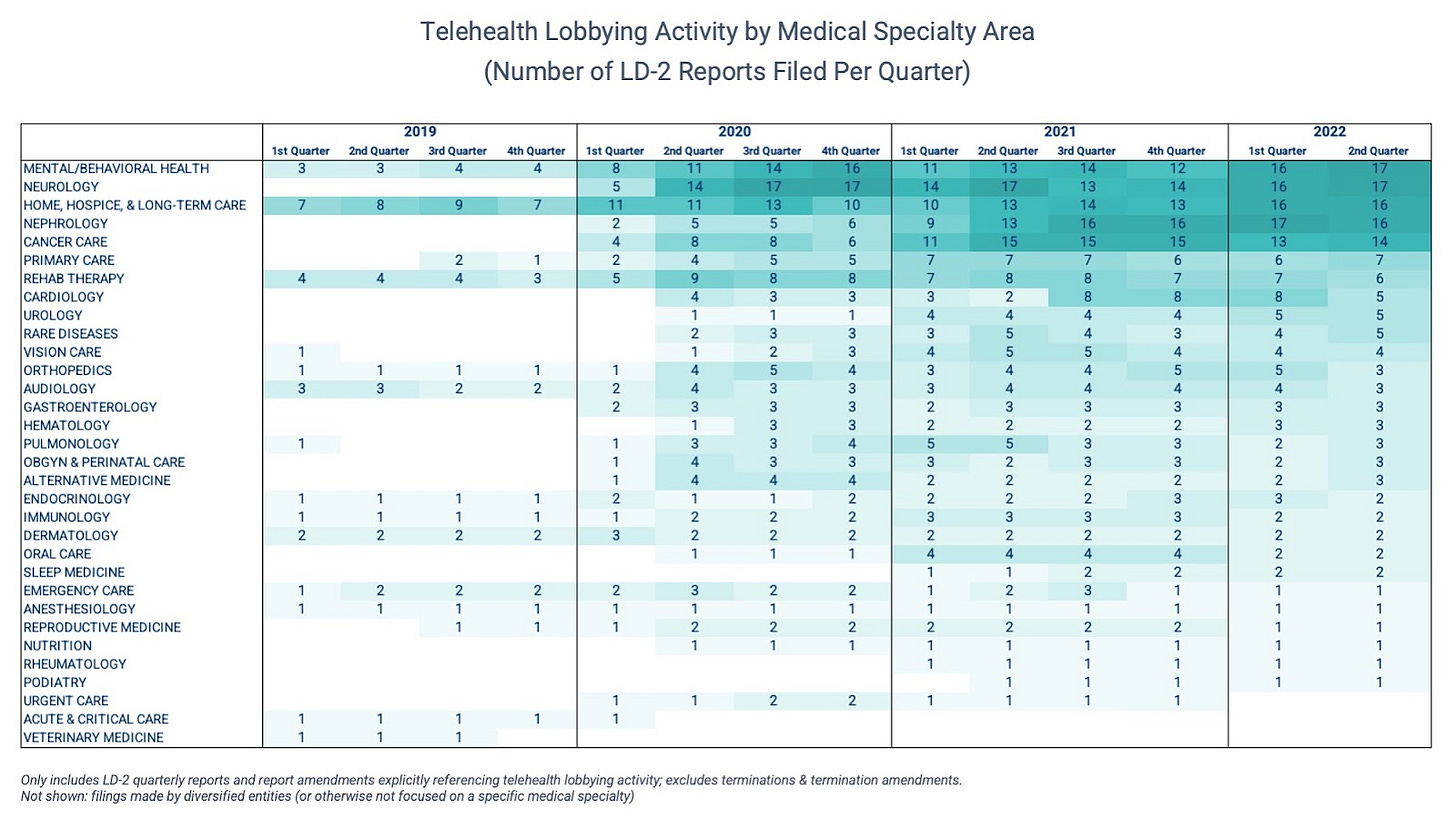

As shown below, medical specialties all across the board are represented on the Hill. But advocacy in four specific areas — mental/behavioral health, neurology, nephrology, and home/hospice/long-term care — has picked up noticeably over the last few quarters.

Telehealth legislative activity

As one would hope, there does seem to be a general correlation between telehealth lobbying activity (number of LD-2 reports filed) and legislative activity (number of bills introduced in Congress).

On the back of record-level lobbying activity, more telehealth-related bills have reached the Congressional floor in the past 2.5 years than the prior 5 years combined. But unfortunately, a smaller percentage are getting signed into law.

So, what’s the hold up? Is this a classic case of partisan gridlock?

For the most part, no.

“The telehealth message in DC is near unanimous,” said Leslie Krigstein, Transcarent’s VP of Government Affairs (who previously held the same role at Livongo, then Teladoc). “That’s what makes it so frustrating that there hasn’t been more Congressional action,” she added.

What everyone seems to agree on is that telehealth is critical for expanded access, and more comprehensive reform is needed to ensure it stays in place permanently. Where you do find some nuance is payment parity, but aside from that, there’s broad alignment on maintaining access.

Most of the big telehealth bills have been bipartisan – “even the aspirational ones that try to do everything,” said Rosen. “It’s not a Republican vs. Democrat barrier; it’s both parties trying to figure out what to do about a very positive development and do good by providers, payers, and patients.”

What has become challenging is figuring out the best way to balance all of those interests… and do it in a way that the federal budget can support.

“Telehealth is the easiest thing to talk about but the hardest thing to do,” said Libby Baney, Partner and Digital Health Co-Chair at Faegre Drinker.

Why? Because you need to think about all the controls that need to be put in place. It’s not as simple as just permanently authorizing the public health emergency waivers because that could have unintended consequences in the long-run.

There’s apprehension, for example, that doing so could diminish incentives for in-person care, which could jeopardize providers’ abilities to make accurate and timely diagnoses.

And then there’s the potential for fraud, waste, and abuse.

Rosen says there might be a bit of overgeneralization happening on the Hill — with senators and lobbyists equating one-off calls to a doctor to prescribe something with legitimate telehealth visits — which could be contributing to slightly exaggerated fears about fraud and abuse. Though there certainly are bad actors out there, they’re present throughout healthcare, not just in the context of telemedicine.

What is true about purely online operations, though, is that it’s easier for them to feign legitimacy.

For example, rogue telemedicine companies/online pharmacies can easily hide their ownership and operations data because domain name registration data is effectively inaccessible/unavailable to the public. [As an aside, the Alliance for Safe Online Pharmacies published a great summary of the issue here.]

But this is something Congress can solve separately from telehealth legislation, which is what groups like the Coalition for a Secure and Transparent Internet (CSTI) are advocating for.

Online prescribing is also a hot button issue because of longstanding fears about controlled substances and potential for abuse.

When the Ryan Haight Act was passed in 2008, telehealth was not a main avenue of healthcare delivery. The problem Congress was trying to solve at that time was the illegal prescribing and dispensing of controlled substances via the internet. In response, Congress required Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA)-licensed practitioners to evaluate patients in person first before prescribing a controlled substance. The law recognizes telemedicine but requires the DEA to establish a “special registration” process via regulation. To date, the DEA has not done so.

Covid-19 fundamentally changed that by prompting the Drug Enforcement Administration to waive the Act’s in-person requirements.

At a very high level, patients and providers have noted substantial benefits from this expanded access. And aside from some specific and highly publicized abuse allegations (e.g. Cerebral), there’s been little evidence that the public health emergency relaxations have led to broad-based diversion and abuse. In fact, according to the Alliance for Safe Online Pharmacies, studies have shown that restricted access and shortage of prescription drugs can actually increase the likelihood of those outcomes.

But unfortunately, the public health emergency waiver will inevitably end, putting millions of patients at risk of losing access to the legitimate and necessary care they got accustomed to during the pandemic.

A more permanent solution is needed, and it actually could be accomplished without Congressional action. As mentioned previously, the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) has the statutory authority to establish a special registration process, which may allow licensed telehealth clinicians to bypass the Ryan Haight Act’s in-person requirement. Back in March, more than 70 organizations including the American Psychiatric Association and the American Telemedicine Association urged the DEA and the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) to get the ball rolling.

Now, almost six months later, there’s been very little progress. And there’s growing concern that there could be a material time gap between the end of the public health emergency waiver and the DEA taking action. During that gap, any virtual care company or provider remotely touching the Ryan Haight Act could be in for a rude awakening, say government affairs experts Baney and Krigstein.

That’s not an immaterial segment of the market. Tons of virtual care startups —particularly those specializing in telepsychiatry and medication-assisted treatment (MAT) — were able to take advantage of these temporary relaxations and, accordingly, raise large sums of capital to expand those business lines over the last few years. Now those businesses could be at risk.

The other issue with reverting back to the Ryan Haight Act at the end of the public health emergency is that it doesn’t effectively address the more threatening byproduct of the internet era: the illegal sale of controlled and counterfeit controlled substances.

One potential solution being proposed is the DRUGS Act, which aims to shut down illegal online sales without restricting patients’ access to otherwise legitimate telehealth and online pharmacies. Similar to the domain name registration transparency issues mentioned previously, the DRUGS Act would target some of the practices of domain name registrars (e.g., GoDaddy).

With respect to waste concerns, one specific example relates to Medicare’s originating site requirements. There’s a big push to remove the requirements completely, but the Congressional Budget Office worries that that could increase utilization — including duplicative and unnecessary — which could unintentionally drive up costs in a fee-for-service environment.

“All the data we have from Teladoc is mostly people under 65,” explained Rosen. There’s far less data on the 65+ population, so without it, the Congressional Budget Office makes assumptions. Rosen illustrated, “So they’re like, ‘Dean Rosen’s father is going to do a telehealth consult with his primary care physician (PCP), and then he’s going to get lonely and still go see his PCP in person. And that’s 2x the cost.’”

But figuring out the appropriate guardrails to counterbalance or curb these risks is not without its challenges.

One area where we’re seeing this play out is in the Senate Finance Committee’s telemental health discussion draft. In the document, they suggest lifting the initial in-person requirement but add some other limitations.

One such condition is that telemental health practitioners would need to show they’re able to see patients in person (or have referral arrangements in place with another physician who can see the patient in person) on the same day as — “or within a reasonable period of time after (as determined appropriate by the Secretary)” — the telehealth visit.

Whether the visit or referral would need to be done the same day needs clarifying, but even if it’s just a referral, that’s still a challenging task for busy providers. Referrals also require insurance information, and a lot of mental healthcare happens outside of that. And if the visit needs to occur the same day, how likely is that to happen, given the provider shortage and the long waitlists patients already face? What would it mean for patients who live in rural areas or those who have physical/psycho/social limitations?

Needless to say, there’s a lot left to be figured out. But the good news is that the ball does continue to roll forward, albeit slowly.

Another development worth mentioning is the Supreme Court’s ruling on Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, which overturned Roe v. Wade and introduced a whole new set of uncertainties for telehealth stakeholders to grapple with. While it’s largely a state (vs. federal) matter, one implication of particular concern is patient privacy afforded under federal law (HIPAA). As currently written, the HIPAA statute has several gaps and gray areas that may unintentionally leave abortion patients vulnerable to law enforcement. President Biden issued an executive order last month urging the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) and the Department of Health and Human Safety (HHS) to consider issuing new regulatory guidance to help address this, but it’s unclear how effective this type of approach would be. It may necessitate Congressional action. But as one of the few areas of telehealth characterized by divisive partisanship, telehealth advocates worry the issue could hinder progress being made on broader legislative reform and are hesitant to muddy the waters.

So, how should healthcare startups think about advocacy?

Well, to start, they shouldn’t be thinking about it as a “nice-to-have.”

Several experts I spoke with argued that it’s practically necessary for businesses operating in an industry as heavily regulated as healthcare — especially those in a relatively nascent and rapidly evolving segment like digital health.

“Investment in government affairs resources is something that you never want to find yourself wishing you had, because at that point, you’re likely behind,” said Krigstein.

The reason being: more often than not, government affairs is aimed at preventing bad stuff from happening; it’s defensive work. And if you don’t invest in those defenses or (at the very least) ensure you’ve got a pulse on the threats looming in the distance, you’re effectively a sitting duck.

Krigstein put it bluntly: “If you aren’t at the table, you are on the menu.”

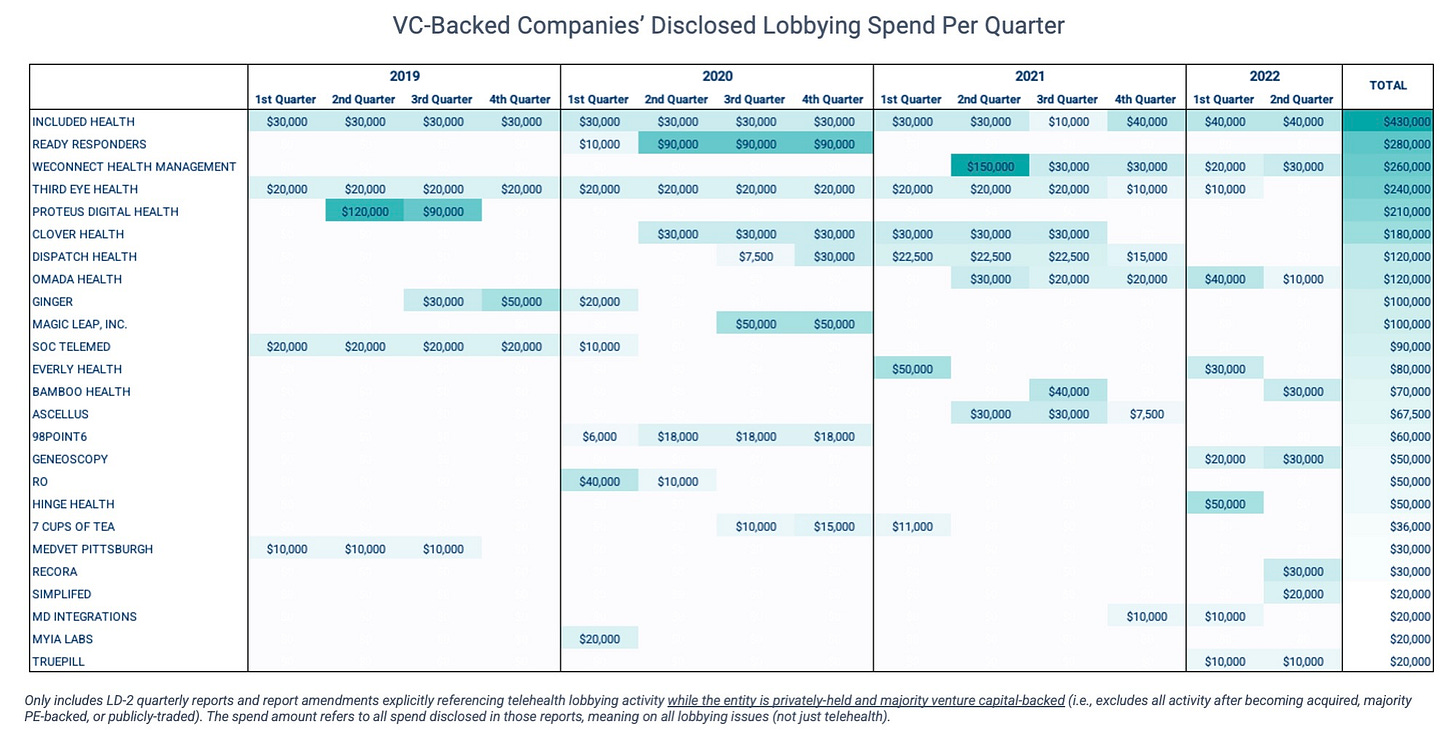

But since it’s far more difficult to quantify the value of preventing possible negative outcomes than the ROI associated with more offensive or proactive wins, there tends to be a misconception that advocacy is a sunk cost. Perhaps this is why we’ve seen VC-backed companies disclose so little in lobbying spend (relative to the sums of capital they’ve raised).

But in a qualitative sense, defensive work can actually “be some of the most impactful investment” a business can make in government affairs, says Baney.

It’s also important for founders, business leaders, and investors to realize that advocacy is inherently a long game. The desired outcomes — by way of policy change — may not be achieved for years, if not decades. And that mentality diverges significantly from what’s typical in the startup world.

The swift actions taken by Congress and the Administration during the early days of the pandemic serve as a helpful reminder of this. “These changes were made possible due to a dedicated group of digital health experts that have been on the frontlines of advocacy for the last decade, long before the pandemic,” explained Krigstein.

What are the different strategies that healthcare companies – particularly startups – can take to influence policy?

Depending on what budgets allow, advocacy generally takes a kitchen sink approach. This can include joining coalitions, hiring third-party lobbyists, bringing a full-time government affairs function in-house, convening at industry conferences, and engaging in thought leadership.

There’s also some heterogeneity across the industry because organizations’ advocacy wants and needs rarely match. “Some companies see [it] as purely risk mitigation, while others may view it as an extension of the commercial function,” explained Krigstein.

For startups specifically, coalitions tend to be a popular avenue because “they’re a bit cheaper than hiring a consultant — and certainly cheaper than hiring a full-time employee — and provide opportunities for smaller/earlier-stage companies to amplify their priorities without publicizing their long-term ambitions,” says consultant Rachel Stauffer.

There’s another benefit to working through trade associations and/or establishing new informal alliances: efficacy. Libby Baney said this approach is actually “highly effective because policymakers tend to listen when diverse groups come together around a shared solution.”

When companies do want to be out in front on particular issues, it’s important to illustrate their differentiation or value-add on the debate. Stauffer explained, “When you go to the Hill, [decision makers] are going to ask ‘how are you different from the 3 other groups I just met with?’ And that’s important when you have a specific ask of them. They need to understand the value you’re bringing, and that can be hard for companies to think through.”

When does it make sense to hire a lobbying firm vs. bring government affairs in-house?

Krigstein says a hybrid approach is ideal, with the in-house team building the agenda and then partnering with an outside firm as part of an executive strategy.

Why? Because each option on its own has notable pluses and minuses.

For example, while an in-house professional always works on the organization’s behalf (vs. a lobbying firm, which has to juggle multiple clients), it’s very difficult for them to maintain the breadth and depth of relationships in DC that a lobbying firm could.

When are lobbying firms a great resource? “When you have a very specific agenda or issue,” said Krigstein. For example, when there’s “an appropriations request, [or] a squeaky wheel inside the administration that doesn’t see the value in your solution… This is when you get great value from a ‘hired gun.’”

But there are important considerations to make in picking a lobbying firm to work with. For example, says Krigstein, “Relationships are always key, so evaluating who the firm works closely with and their proximity to decision makers is a no-brainer. There’s also the element of willingness to understand your business and goals, and accommodate the fast-paced environment of an earlier stage company.” Sometimes that means it’s better to go with a smaller, nimbler firm vs. a bigger “brand name.”

Reflections from the rabbit hole

So after spending a few months digging into this, here’s what I came away with:

- There’s actually consensus about something in DC: substantial legislative reform is needed to secure telehealth’s permanency within the US healthcare system.

- But there’s a lot of pressure to get that reform right. Congress is currently weighing several interdependent counterbalances — and only has enough empirical data right now to support some of them.

- Entities from all corners of the healthcare industry — non-profit and for-profit, publicly-traded and privately-held, payers and providers, etc. — are increasingly stepping up to the plate to provide that evidence and push the ball forward.

- For-profit entities are more engaged than they’ve ever been as the risk/reward calculus has become more tangible on the back of the pandemic.

- In healthcare, having a government affairs strategy is not a “nice-to-have.” It’s a “need-to-have.” Budgets don’t have to be exorbitant to make an impact and there are several avenues companies can take based on their specific constraints, needs, and interests. But advocacy requires a mindset adjustment: it’s inherently a long game. Companies shouldn’t expect to see results overnight.

Appendix: A caveat on for-profit lobbying data

Importantly, the data shown above only counts the for-profit entities we can directly attribute LD-2 filings to. But many more are involved in telehealth advocacy – they just do so in degrees we can’t empirically trace well.

Federal disclosure is only required when lobbying spend surpasses certain thresholds: $3k/quarter when an outside lobbying firm is used and $13k/quarter when managed in-house. And as we discussed, many for-profit entities work through non-profit industry associations, coalitions, etc. which submit their own LD-2 reports and aren’t required to disclose affiliated organizations (unless they are actively involved in and contribute $5k+ to lobbying in the quarter).

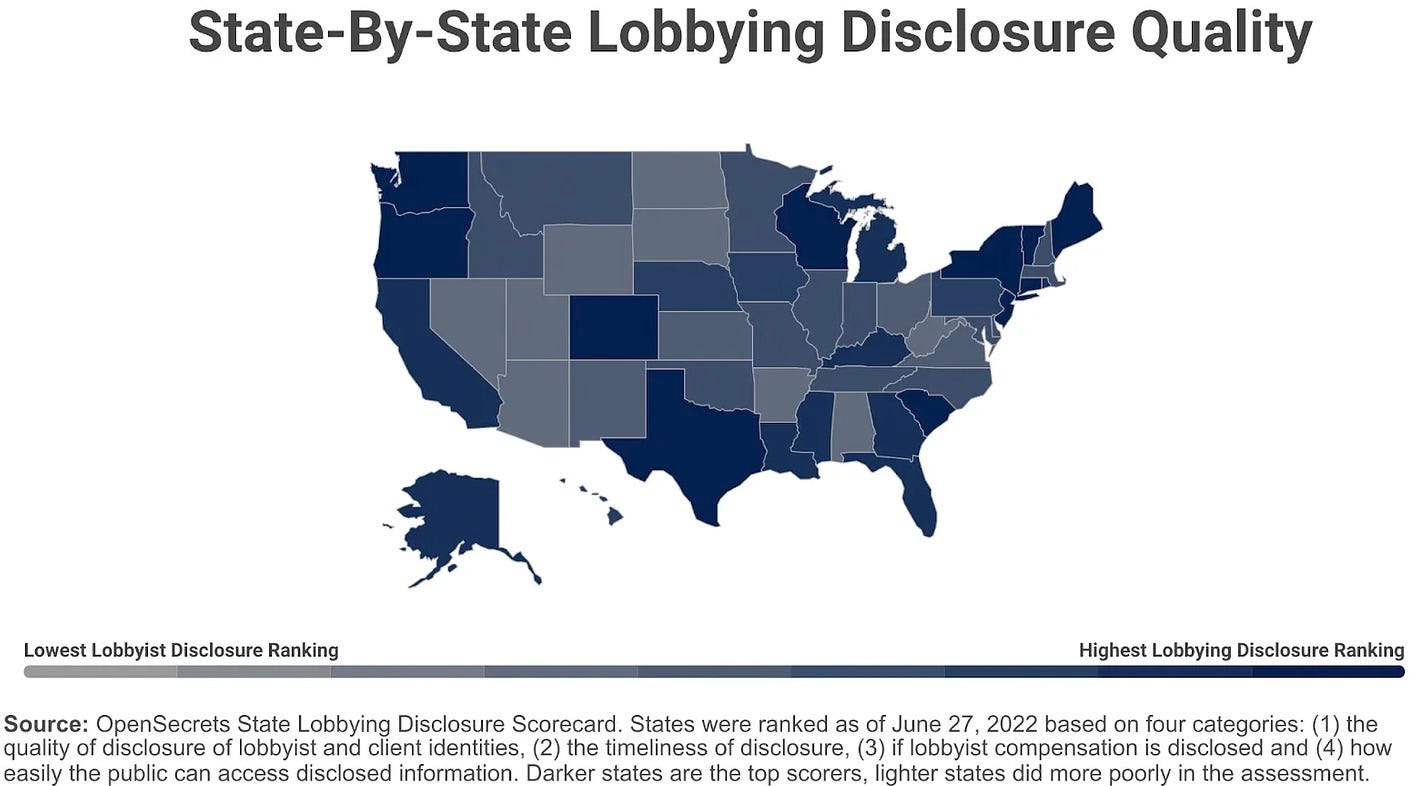

Additionally, even those not lobbying on the Hill can be very actively involved at state and local levels. Teladoc, for example, lobbied aggressively at the state level for years and years before the pandemic. In fact, it wasn’t until the Covid-19 public health emergency that the company hired a full-time federal government affairs rep and started making a concerted push in Washington. But state jurisdictions have different reporting requirements. And while they all have some information available online, the quality of those sites and the data contained within them is highly variable.